The Burrow

Remember the last time you sighed that sweet sigh of relief when it all worked out? Like the time when that alien invasion was fake? Or when the world didn’t end in the year 2000 (or 2012)?

With 2020 throwing everything our way, it’s understandable that many of us are experiencing anxiety. Unfortunately, anxiety can cause panic over certain things that don’t look so bad in hindsight (think toilet roll or baking supplies).

So, we’ve gone back in time to look at seven cases of panic that were – thankfully – anticlimactic. We examine what caused such panic, how the concern was encouraged, and how the public responded to these cases.

As we delve into these events, we recognise that it’s easy to sit on this side of history and wonder how something as simple as, say, dents in a windshield could cause mass hysteria.

As we step back, let’s do so in the shoes of society at the time, and wonder how we may react in these scenarios. We feel such a mindset is crucial, especially since 2020 has provided challenges that may look different for each person across the globe.

Sources: 1-6

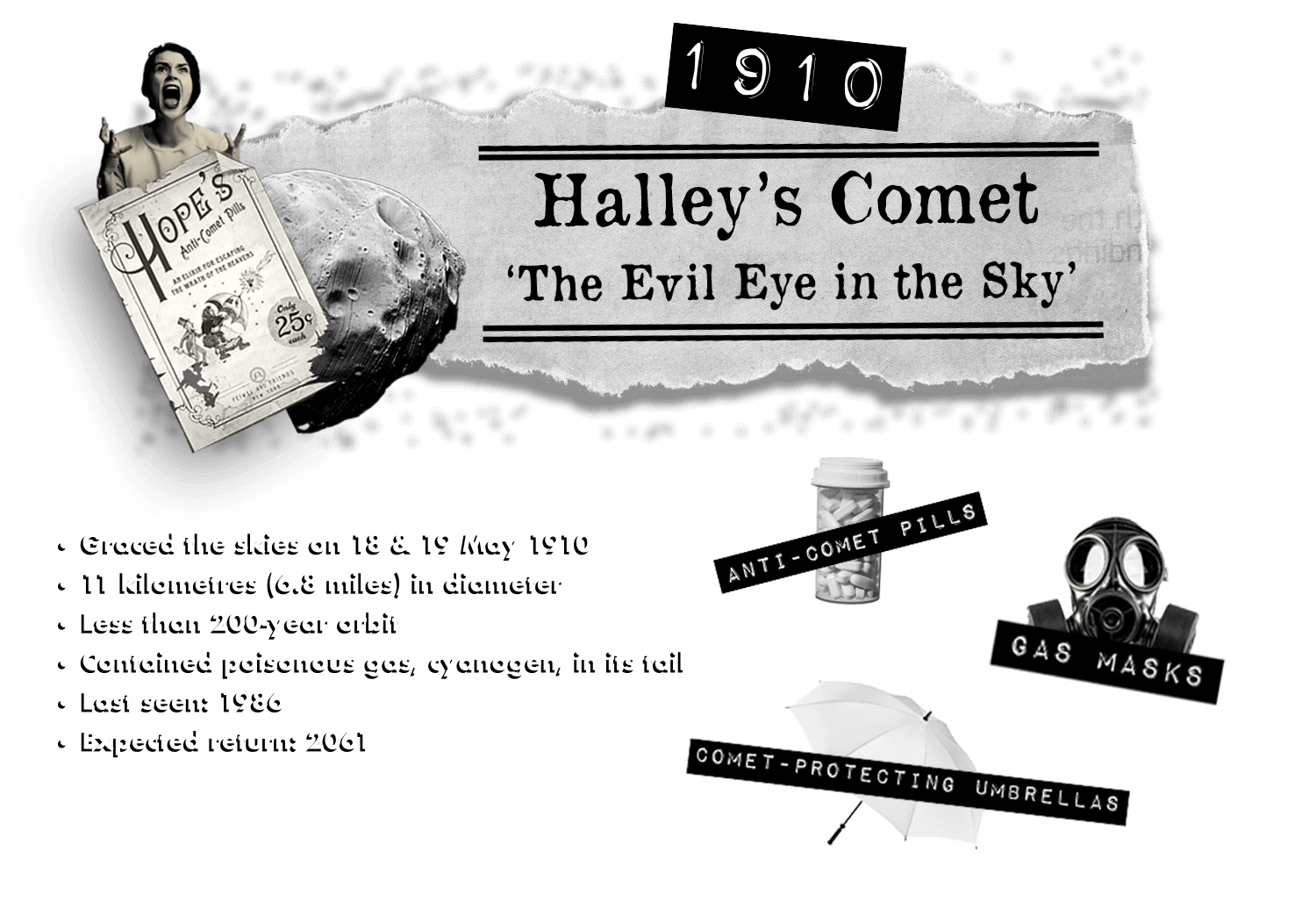

Leading up to May 1910, many civilians and astronomers alike were searching the skies in nervous anticipation, fearful of what could happen to Earth when Halley’s Comet passed by.

Would it offer a beautiful show? Or would its tail engulf the world in a poisonous gas?

It had been a long 75 years since Halley’s Comet had graced the skies. Come September 1909, and news started circulating about its arrival.

French astronomer, Camille Flammarion, said that the poisonous gas, cyanogen, in the comet’s tail would ‘snuff out’ all life on Earth when it passed by.7,8

Naturally, this created its fair share of mass hysteria.

Scientists were encouraged to keep an eye out for ‘abnormal atmospheric phenomena’, according to D W Hughes in his piece titled ‘The History of Halley’s Comet’. Scientific balloons were launched into the sky, and meteor watches began.9

Source: 11

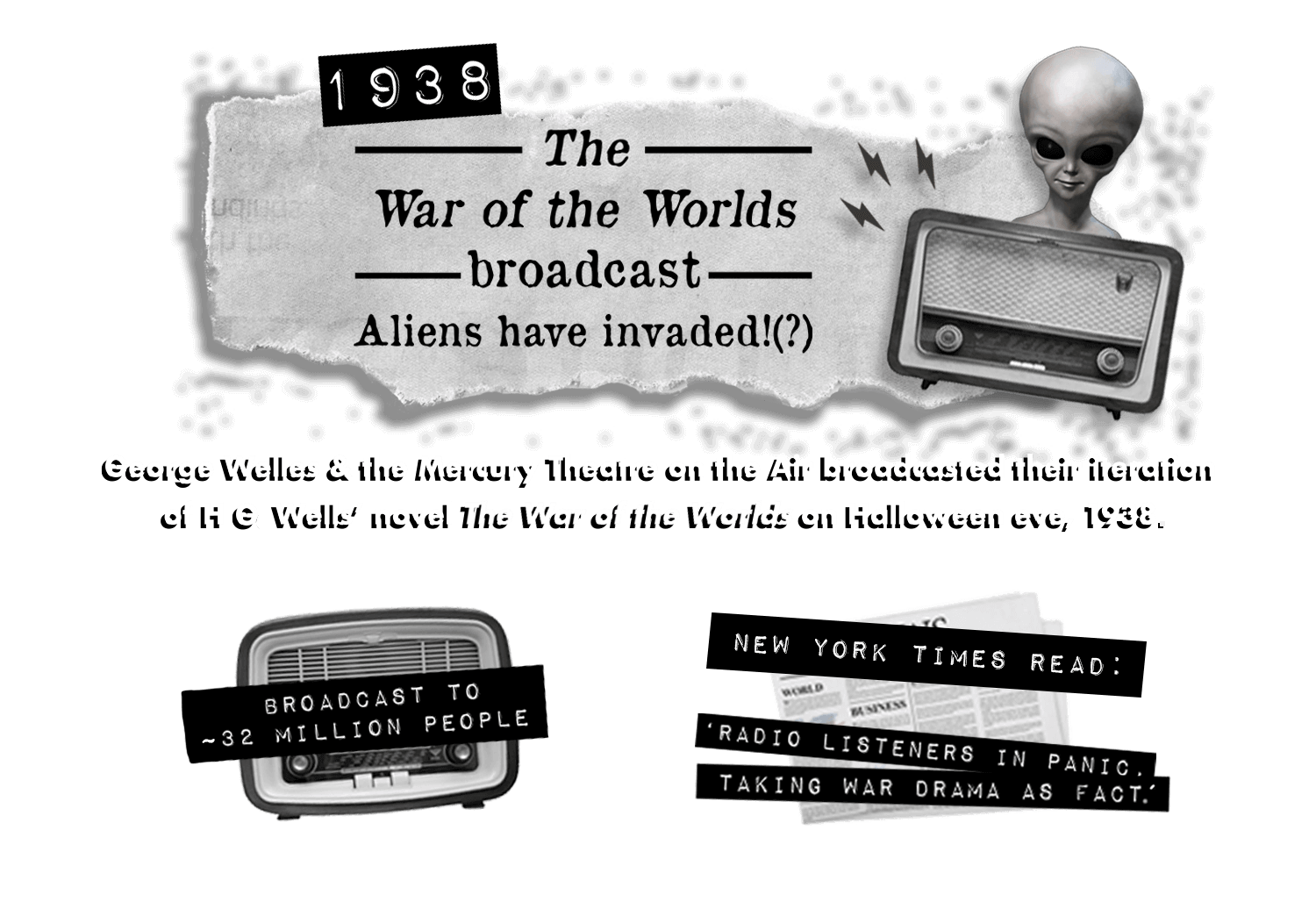

It’s Halloween eve, 1938. Amidst the spiderwebs, goblins and ghosts decorating your street, all is quiet. You pop upstairs to your apartment and turn on the radio as you get dinner sorted. Ballroom music fills your kitchen.11

It’s not long before the orchestra’s cut short with a bulletin. You pause and listen through the broadcasts.

Well, then! It seems aliens have invaded New Jersey.

Assistant Professor Claire Ahn at Queen’s University, Ontario, explained that the radio play mimicked a typical radio broadcast: it started with talk of the weather, and then it moved onto ballroom music. Then, reports of the invasion filtered in.13

In his article, ‘The Fake News of Orson Welles’, Peter Tonguette explained that Welles spoke as if he were a reporter from 30 October 1939. This date was a whole year away from the date the play was broadcasted.

The overall perception was that the Welles’ radio play had caused mass hysteria. Even though the program was first presented as a fake broadcast from the future, some of the public really thought that there was an invasion going on in New Jersey.

Though, it seemed that the play’s futuristic date went over listeners’ heads – or was perhaps missed by listeners who tuned in late.

Media scholars Jefferson Pooley and Michael J Socolow believe the hysteria was hyped up, as explained in Ahn’s article.14

It seems some newspapers were trying to ‘discredit broadcast media’.

Given how well Welles had followed typical broadcast patterns and the wartime climate, some of his audience, it seems, believed.

Sources: 15-17

On 24 June 1947, private pilot and businessman, Kenneth Arnold, spotted ‘disc-shaped’ objects travelling in the air near Mt Rainier in Washington.18

Soon, reports were flooding in of additional sightings, from military and civilian pilots and air traffic control.

Theories and conspiracies were running rampant – and still are, to this day.

Known as ‘unidentified flying objects’ – or UFOs – the Air Force said that while these objects were real, they were ‘easily explained’.

In fact, according to the CIA, the Air Force explained that almost all sightings stemmed from a misinterpretation of known objects. However, they also reported that these objects were also borne of mass hysteria, hallucinations or hoaxes.19

Even so, the Air Force recommended continued investigation from the military – and didn’t rule out ‘extraterrestrial phenomena’.

The public’s uncertainty was heightened due to the Cold War and the ‘confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union’.20

Due to the CIA’s fear of ‘increased Soviet capabilities’, the CIA Study Group believed these flying saucers posed a level of national security. They believed the Soviets could use UFO reports to create mass hysteria and panic in the US.

On 7 July 1947, north of Roswell in New Mexico, William Brazel discovered debris on a ranch. Wondering if this was part of a flying saucer, he alerted authorities. The Roswell Daily Record said the RAAF (Roswell Army Air Field) had indeed captured a flying saucer.21

According to archivists Dr Greg Bradsher and Dr Sylvia Naylor, this debris was from a ‘highly classified project used by the United States Army Air Force (USAAF)’. The debris was used to detect atomic bomb tests in the Soviet Union.22

However, after the ‘Roswell incident’, reports of flying saucers were made in 44 states and other countries.23

Sources: 24, 25

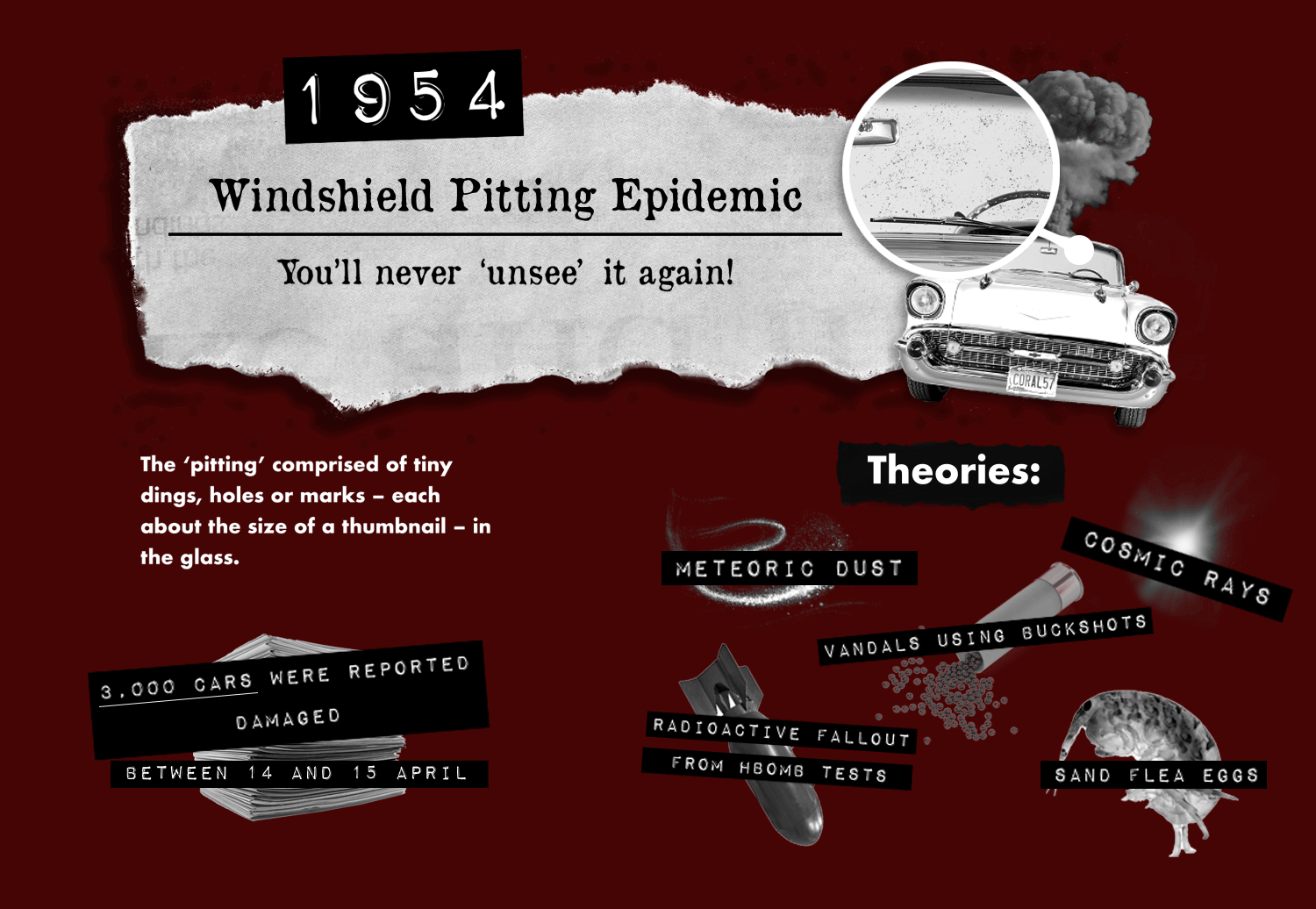

It’s mid-April, 1954. You’re driving towards Washington’s Fidalgo Island as Sinatra croons on the radio. Life is good!

As you reach the Deception Pass Bridge,26 a police officer instructs you to pull up behind a line of other cars. He makes his way over and squints at your windscreen.

‘Yep, we’ve got another one!’ the officer yells to his partner. ‘The glass is all pitted, see?’

You lower your sunglasses and look closer at your windshield. Suddenly, you see it, almost forming right before your eyes; imperfections, all throughout your windshield.

But… how?

Welcome to the windshield pitting epidemic of Seattle.

Historian Alan J Stein noted that the Mayor of Seattle appealed for help from the Governor and President Eisenhower as the reports grew.27

Public perception of the pitting?

Whidbey Island’s Sheriff Tom Clark suggested that radioactivity released by hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) were causing these issues. These tests had taken place earlier in March in the South Pacific.

Medalia and Larsen hypothesised in their book that the rising concern of damage was relative to the newspaper column width dedicated to the issue.

Medalia and Larsen revealed that 31% of believers surveyed attributed the pitting to H-bomb explosions.28

According to their findings:

Some newspapers voiced the idea that drivers were looking at their windshields for the first time, not through them.29

Ultimately, the pitting was always there!

Sources: 30, 31

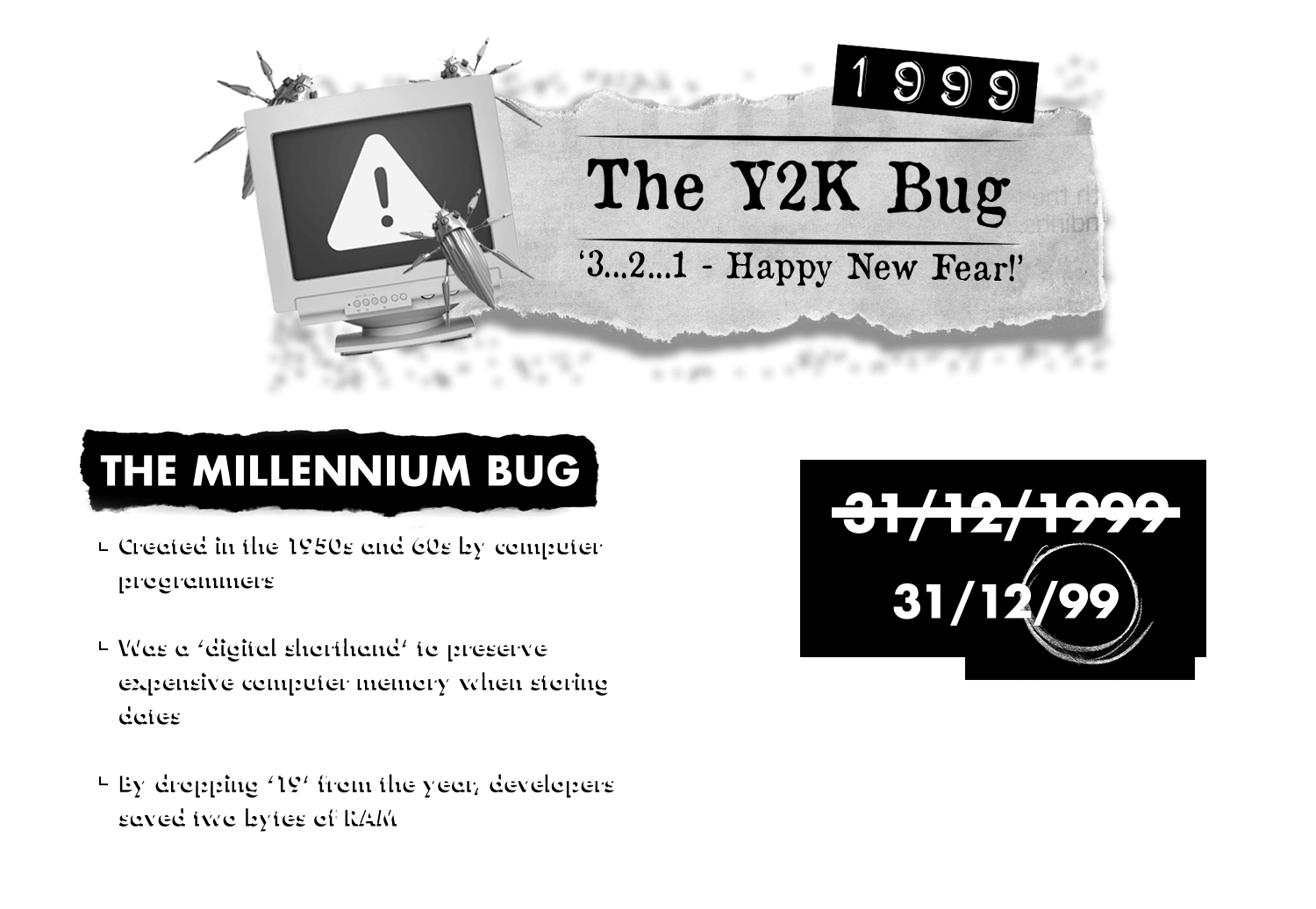

On 31 December 1999, some sipped champagne and counted down to the new millennium in high spirits. Others had their battery-powered torches at the ready, and their bathtubs were rippling at the brim.

Would countries erupt into chaos, one by one, as the world rotated into the year 2000? These fears were fueled by concerns that at the stroke of midnight:

• planes could fall from the sky;

• banking and accounting would fail;

• elevators may plummet to the ground;

• nuclear plants could malfunction; and

• pacemakers could stop ticking.32

According to the Special Committee of the Year 2000 Technology Problem, the least prepared for the Y2K included:

50% of small to medium-sized businesses had addressed the Y2K.33

The International Y2K Cooperation Center explained that the domestic and international public opinion was sceptical about the readiness of the Y2K.34

Many news sources were offering extreme views of the situation. Sentiment ranged from assertions like ,‘Get your Y2K go-bag ready!’ to ‘Y2K: Hoax just to buy new technology’.

The US Department of Commerce’s 1999 report revealed Air Vietnam had a vintage aircraft that hadn’t been cleared of Y2K errors. As such, the company decided they wouldn’t fly on New Year’s Eve or on 1 January 2000.

The report led to residual fears with the demand for flights decreasing over the New Year’s Eve weekend. The public was worried, even though companies like Boeing and Airbus had spent around $2.3 billion to prepare for Y2K.35

It seemed greater communication and transparency helped quell some fears, based on the results from multiple Gallup surveys on the subject.

Though, the surveyed American public remained quite torn over the readiness of air travel and banking. Specifically, 43% of respondents said they’d avoid travelling on planes as 1 January 2000 approached.36

Source: 36

Planes did not fall from the sky, and nuclear weapons were not deployed. Japan did experience minor glitches at a power plant. Aside from small issues here and there across the globe, the world didn’t go dark.40

In short, the efforts to prepare for Y2K paid off.

Source: 41

Dr Williams explained that ‘the distance to the planets is too great for their gravity, magnetic fields, radiation, etc., to have any discernible effect on the earth’.42

Another event like this on 4 February 1962 produced similar fears – particularly in astrologers and students of Nostradamus.

NASA’s article titled ‘Planets for Dessert’ explained that in 1962, the sun, moon and planets from Mercury to Saturn were clustered within a 17-degree area of sky on this date. It even produced a total eclipse of the sun.43

Nothing happened then, either; no misfortune could spoil the view of the eclipse.

The next planetary alignment is predicted for 8 September 2040.

Sources: 44

The lead up to 21 December 2012 should have been a time where holidaymakers were decking the halls and sipping eggnog. However, some worried that Roland Emmerich’s 2012 action flick just might leap off the screen and into reality.

In short, the world was going to end on 21 December 2012.

‘There’s no Planet Nibiru, there’s no “Planet X”, and nothing is hurtling towards us,’ said Donald Yeomans, manager of NASA’s Near-Earth Object Office in 2012.45

The Mayan calendar’s 13th baktun (a cycle comprising of around 394 years) was ending on 21 December 2012.46

This stoked fears that the world would end with it.

However, the new Mayan calendar cycle was due to begin on 22 December 2012 – just like a new calendar year begins on 1 January.47

David Morrison, Senior Scientist at NASA Lunar Science Institute, explained that the ancient Maya did not predict the end of the world or any disaster to occur on 21 December 2012. It was all a hoax.48

On increased solar activity, NASA’s Donald Yeomans explained that the sun goes through its own cycles, reaching a maximum activity every 11 years.

There was no reason why 2012 had to be any different to those previous cycles.49

A 2012 Ipsos media release revealed what 16,262 adults over 21 countries thought of the ‘impending doom’.50

On whether they believed that the end of the Mayan calendar marked the end of the world:

On which countries appeared most anxious from a perceived ‘end of the world’ in 2012:

Nobody can foresee life’s twists and turns – especially those in 2020.

However, we can look back on stressful past events and take heart from society’s strength – even during times that may seem quite absurd to us today.

While we may not be able to help with UFO sightings or doomsday predictions, we can empower you to prepare for those other bumps in the road; especially when it comes to your physical and mental health and wellbeing.

Discover how a competitive health insurance policy can offer you more choice in your treatment to help cover the whole family.

SOURCES

Brought to you by Compare the Market: Making it easier for Australians to search for great deals on Health Insurance.